Don’t Repeat Yourself

For such a common use case as appending a semicolon at the end of a series of lines, Vim provides a dedicated command that combines two steps into one

Suppose that we have a snippet of JavaScript code like this:

1

2

3

var foo = 1

var bar = 'a'

var foobar = foo + bar

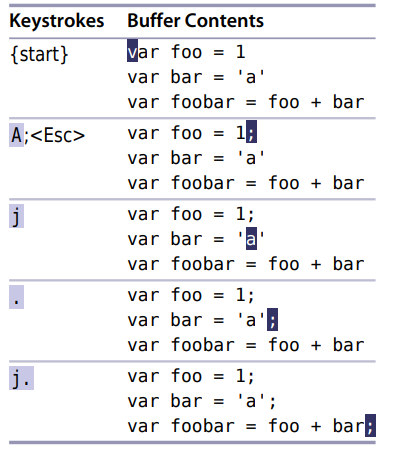

We need to append a semicolon at the end of each line. Doing so involves moving our cursor to the end of the line and then switching to Insert mode to make the change. The $ command will handle the motion for us, and then we can run a;

To finish the job, we could run the exact same sequence of keystrokes on the next two lines, but that would be missing a trick. The dot command will repeat that last change, so instead of duplicating our efforts, we could just run j$. twice. One keystroke (.) buys us three (a;

But let’s take a closer look at this pattern: j$.. The j command moves the cursor down one line, and then the $ command moves it to the end of the line. We’ve used two keystrokes just to maneuver our cursor into position so that we can use the dot command. Do you sense that there’s room for improvement here?

Reduce Extraneous Movement

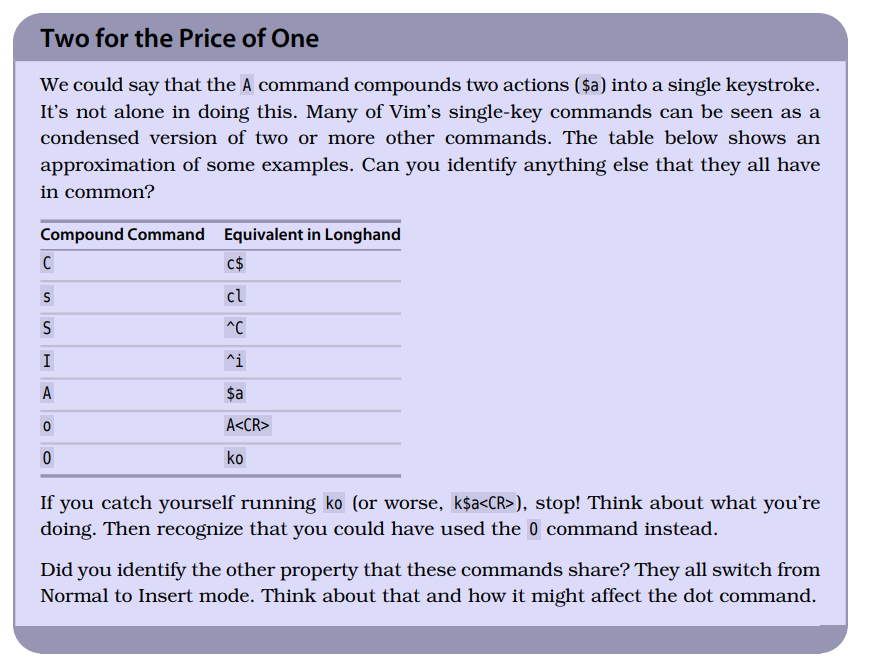

While the a command appends after the current cursor position, the A command appends at the end of the current line. It doesn’t matter where our cursor is at the time, pressing A will switch to Insert mode and move the cursor to the end of the line. In other words, it squashes $a into a single keystroke. In Two for the Price of One, on page 6, we see that Vim has a handful of compound commands.

Here is a refinement of our previous example:

By using A instead of $a, we give the dot command a boost. Instead of having to position the cursor at the end of the line we want to change, we just have to make sure it is somewhere (anywhere!) on that line. Now we can repeat the change on consecutive lines just by typing j. as many times as it takes.

One keystroke to move, another to execute. That’s about as good as it gets! Watch for this pattern of usage, because we’ll see it popping up in a couple more examples.

Although this formula looks terrific for our short example, it’s not a universal solution. Imagine if we had to append a semicolon to fifty consecutive lines. Pressing j. for each change starts to look like a lot of work. For an alternative approach, skip ahead to Tip 30,Run Normal Mode Commands Across a Range, on page 63.

Take One Step Back, Then Three Forward

We can pad a single character with two spaces (one in front, the other behind) by using an idiomatic Vim solution. At first it might look slightly odd, but the solution has the benefit of being repeatable, which allows us to complete the task effortlessly.

Suppose that we have a line of code that looks like this:

1

var foo = "method("+argument1+","+argument2+")";

Concatenating strings in JavaScript never looks pretty, but we could make this a little easier on the eye by padding each + sign with spaces to make it look like this:

1

2

var foo = "method(" + argument1 + "," + argument2 + ")";

Make the Change Repeatable

This idiomatic approach solves the problem:

The s command compounds two steps into one: it deletes the character under the cursor and then enters Insert mode. Having deleted the + sign, we then type ␣+␣ and leave Insert mode.

One step back and then three steps forward. It’s a strange little dance that might seem unintuitive, but we get a big win by doing it this way: we can repeat the change with the dot command; all we need to do is position our cursor on the next + symbol, and the dot command will repeat that little dance.

Make the Motion Repeatable

There’s another trick in this example. The f{char} command tells Vim to look ahead for the next occurrence of the specified character and then move the cursor directly to it if a match is found (see :h f ). So when we type f+, our cursor goes straight to the next + symbol. We’ll learn more about the f{char} command in Tip 50,Find by Character, on page 120.

Having made our first change, we could jump to the next occurrence by repeating the f+ command, but there’s a better way. The ; command will repeat the last search that the f command performed. So instead of typing f+ four times, we can use that command once and then follow up by using the ; command three times.

All Together Now

The ; command takes us to our next target, and the . command repeats the last change, so we can complete the changes by typing ;. three times. Does that look familiar?

Instead of fighting Vim’s modal input model, we’re working with it, and look how much easier it makes this particular task

Act, Repeat, Reverse

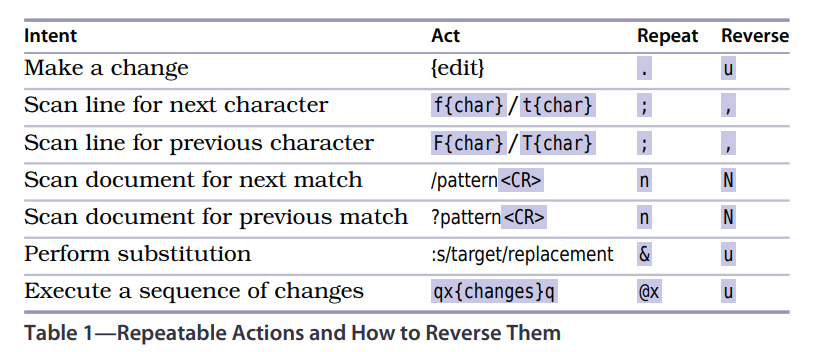

When facing a repetitive task, we can achieve an optimal editing strategy by making both the motion and the change repeatable. Vim has a knack for this. It remembers our actions and keeps the most common ones within close reach so that we can easily replay them. In this tip, we’ll introduce each of the actions that Vim can repeat and learn how to reverse them.

We’ve seen that the dot command repeats the last change. Since lots of operations count as a change, the dot command proves to be versatile. But some commands can be repeated by other means. For example, @: can be used to repeat any Ex command (as discussed in Tip 31,Repeat the Last Ex Command, on page 65). Or we can repeat the last :substitute command (which itself happens to be an Ex command as well) by pressing & (see Tip 93,Repeat the Previous Substitute Command, on page 229).

If we know how to repeat our actions without having to spell them out every single time, then we can be more efficient. First we act; then we repeat

But when so much can be achieved with so few keystrokes, we have to watch our step. It’s easy to get trigger-happy. Rapping out j.j.j. again and again feels a bit like doing a drum roll. What happens if we accidentally hit the j key twice in a row? Or worse, the . key?

Whenever Vim makes it easy to repeat an action or a motion, it always provides some way of backing out in case we accidentally go too far. In the case of the dot command, we can always hit the u key to undo the last change. If we hit the ; key too many times after using the f{char} command, we’ll miss our mark. But we can back up again by pressing the , key, which repeats the last f{char} search in the reverse direction (see Tip 50,Find by Character, on page 120).

It always helps to know where the reverse gear is in case you accidentally go a step too far. Table 1, Repeatable Actions and How to Reverse Them, on page 9, summarizes Vim’s repeatable commands along with their corresponding reverse action. In most cases, the undo command is the one that we reach for. No wonder the u key on my keyboard is so worn out!

Find and Replace by Hand

Vim has a :substitute command for find-and-replace tasks, but with this alternative technique, we’ll change the first occurrence by hand and then find and replace every other match one by one. The dot command will save us from labor, but we’ll meet another nifty one-key command that makes jumping between matches a snap.

In this excerpt, the word “content” appears on every line:

1

2

3

...We're waiting for content before the site can go live...

...If you are content with this, let's go ahead with it...

...We'll launch as soon as we have the content...

Suppose that we want to use the word “copy” (as in “copywriting”) instead of “content.” Easy enough, you might think; we can just use the substitute command, like this:

1

:%s/content/copy/g

But wait a minute! If we run this command, then we’re going to create the phrase “If you are ‘copy’ with this,” which is nonsense!

We’ve run into this problem because the word “content” has two meanings. One is synonymous with “copy” (and pronounced content), the other with “happy” (pronounced content). Technically, we’re dealing with heteronyms (words that are spelled the same but differ in both meaning and pronunciation), but that doesn’t really matter. The point is, we have to watch our step

We can’t just blindly replace every occurrence of “content” with “copy.” We have to eyeball each one and answer “yay” or “nay” to the question, should this occurrence be changed? The substitute command is up to the task, and we’ll find out how in Tip 90,Eyeball Each Substitution, on page 223. But right now, we’ll explore an alternative solution that fits with the theme of this chapter.

Be Lazy: Search Without Typing

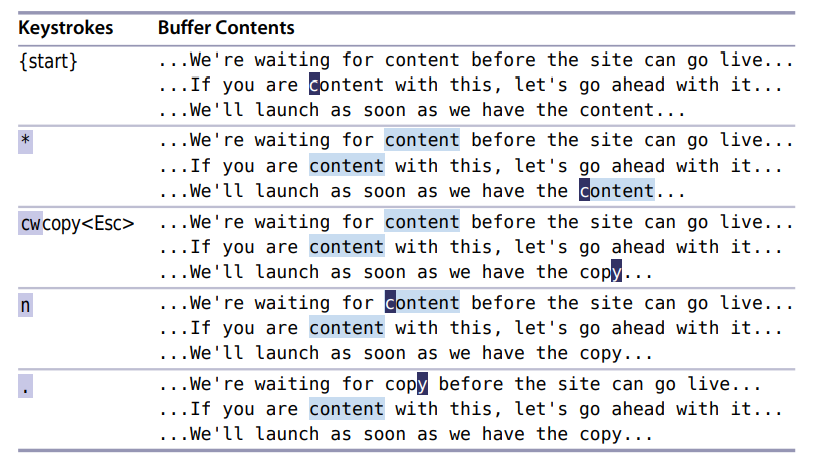

You might have guessed by now that the dot command is my favorite singlekey Vim trigger. In second place is the * command. This executes a search for the word under the cursor at that moment (see :h * ).

We could search for the word “content” by pulling up the search prompt and spelling out the word in full:

1

/content

Or we could simply place our cursor on the word and hit the * key. Consider the following workflow:

We begin with our cursor positioned on the word “content” and then use the * command to search for it. Try it for yourself. Two things should happen: the cursor will jump forward to the next match, and all occurrences will be highlighted. If you don’t see any highlighting, try running :set hls and then refer to Tip 81,Highlight Search Matches, on page 204, for more details.

Having executed a search for the word “content,” we can now advance to the next occurrence just by hitting the n key. In this case, pressing *nn would cycle through all matches, taking us back to where we started.

Make the Change Repeatable

With our cursor positioned at the start of the word “content,” we are poised to change it. This involves two steps: deleting the word “content” and then typing its replacement. The cw command deletes to the end of the word and then drops us into Insert mode, where we can spell out the word “copy.” Vim records our keystrokes until we leave Insert mode, so the full sequence cwcopy

All Together Now

We’re all set! Each time we press the n key, our cursor advances to the next occurrence of the word “content.” And when we press the . key, it changes the word under the cursor to “copy.”

If we wanted to replace all occurrences, we could blindly hammer out n.n.n. as many times as it took to complete all the changes (although in that case, we might as well have used the :%s/content/copy/g command). But we need to watch out for false matches. So after pressing n, we can examine the current match and decide if it should be changed to “copy.” If so, we trigger the . command. If not, we don’t. Whatever our decision, we can then move on to the next occurrence by pressing n again. Rinse and repeat until done.

Meet the Dot Formula

We’ve considered three simple editing tasks so far. Even though each problem was different, we found a solution using the dot command for each one. In this tip, we’ll compare each solution and identify a common pattern—an optimal editing strategy that I call the Dot Formula.

Reviewing Three Dot-Command Editing Tasks

In Tip 2,Don’t Repeat Yourself, on page 4, we wanted to append a semicolon at the end of a sequence of lines. We changed the first line by invoking A;

In Tip 3,Take One Step Back, Then Three Forward, on page 6, we wanted to pad each occurrence of the + symbol with a space both in front and behind. We used the f+ command to jump to our target and then the s command to substitute one character with three. That set us up so that we could complete the task by pressing ;. a few times.

In Tip 5,Find and Replace by Hand, on page 9, we wanted to substitute every occurrence of the word “content” with the word “copy.” We used the * command to initiate a search for the target word and then ran the cw command to change the first occurrence. This set us up so that the n key would take us to the next match and the . key would apply the same change. We could complete the task simply by pressing n. as many times as it took.

The Ideal: One Keystroke to Move, One Keystroke to Execute

In all of these examples, using the dot command repeats the last change. But that’s not the only thing they share. A single keystroke is all that’s required to move the cursor to its next target.

We’re using one keystroke to move and one keystroke to execute. It can’t really get any better than that, can it? It’s an ideal solution. We’ll see this editing strategy coming up again and again, so for the sake of convenience, we’ll refer to this pattern as the Dot Formula.