Exploring the system

Now that we know how to move around the file system, it’s time for a guided tour of our Linux system. Before we start, however, we’re going to learn some more commands that will be useful along the way.

1

2

3

ls List directory contents

file Determine file type

less View file contents

More Fun with ls

The ls command is probably the most used command, and for good reason. With it, we can see directory contents and determine a variety of important file and directory attributes.As we have seen, we can simply enter ls to get a list of files and subdirectories contained in the current working directory.

1

2

[me@linuxbox ~]$ ls

Desktop Documents Music Pictures Public Templates Videos

Besides the current working directory, we can specify the directory to list, like so

1

2

me@linuxbox ~]$ ls /usr

bin games include lib local sbin share src

We can even specify multiple directories. In the follwing example, we list both the user’s home directory (symbolized by the ~ chracter) and the /usr directory:

1

2

3

4

5

[me@linuxbox ~]$ ls ~ /usr

/home/me:

Desktop Documents Music Pictures Public Templates Videos

/usr:

bin games include lib local sbin share src

We can also change the format of the output to reveal more detail

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

[me@linuxbox ~]$ ls -l

total 56

drwxrwxr-x 2 me me 4096 2017-10-26 17:20 Desktop

drwxrwxr-x 2 me me 4096 2017-10-26 17:20 Documents

drwxrwxr-x 2 me me 4096 2017-10-26 17:20 Music

drwxrwxr-x 2 me me 4096 2017-10-26 17:20 Pictures

drwxrwxr-x 2 me me 4096 2017-10-26 17:20 Public

drwxrwxr-x 2 me me 4096 2017-10-26 17:20 Templates

drwxrwxr-x 2 me me 4096 2017-10-26 17:20 Videos

by adding -l to the command, we chagne the output to the long format.

Options and Arguments

This brings us to a very important point about how most commands work.

Commands are often followed byu one or more options that modify their behavior and, further, by one or more argumenmts, the items upon which the command acts. So, most commands look kind of like this:

1

command -options arguments

Most commands use options, which consist of a single character preceded by a dash, for example, -l. Many commands, however, including those from the GNU Project, also support long options, consisting of a word preceded by two dashes. Also, many commands allow multiple short options to be strung together. In the following example, the ls command is given two options, which are the l option to produce long format output, and the t option to sort the result by the file’s modification time.

1

[me@linuxbox ~]$ ls -lt

We’ll add the long option –reverse to reverse the order of the sort.

1

[me@linuxbox ~]$ ls -lt --reverse

Command options, like filenames in Linux, are case sensitive.

The ls command has a large number of possible options, the most common of which are listed in Table 3-1.

A Longer Look at Long Format

As we saw earlier, the -l option causes ls to display its results in long format. This format contains a great deal of useful information. Here is the Examples directory from an Ubuntu system:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 3576296 2017-04-03 11:05 Experience ubuntu.ogg

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1186219 2017-04-03 11:05 kubuntu-leaflet.png

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 47584 2017-04-03 11:05 logo-Edubuntu.png

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 44355 2017-04-03 11:05 logo-Kubuntu.png

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 34391 2017-04-03 11:05 logo-Ubuntu.png

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 32059 2017-04-03 11:05 oo-cd-cover.odf

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 159744 2017-04-03 11:05 oo-derivatives.doc

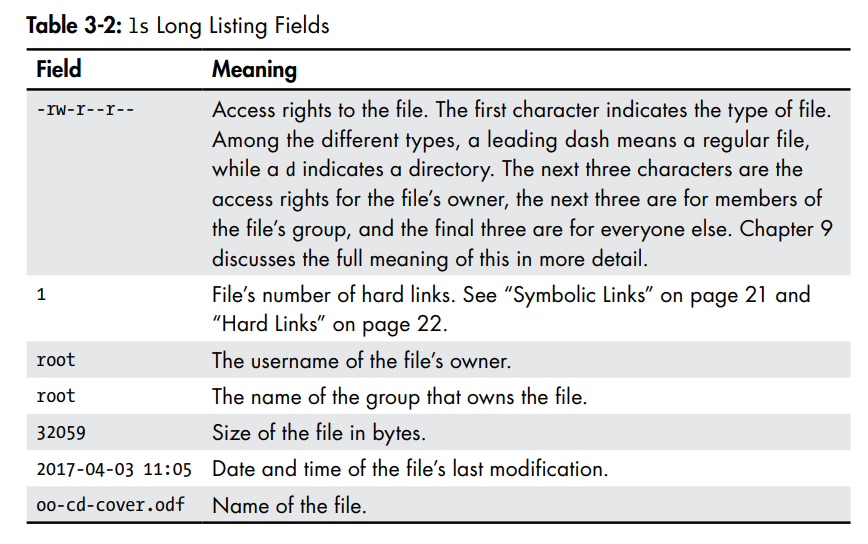

Table 3-2 provides us with a look at the different fields from one of the files and their meanings

Determining a File’s Type with file

As we explore the system, it will be useful to know what files contain. To do this, we will use the file command to determine a file’s type. As we discussed earlier, filenames in Linux are not required to reflect a file’s contents. While a filename like picture.jpg would normally be expected to contain a JPEG-compressed image, it is not required to in Linux. We can invoke the file command this way:

1

file filename

When invoked, the file command will print a brief description of the file’s contents. For example:

1

2

[me@linuxbox ~]$ file picture.jpg

picture.jpg: JPEG image data, JFIF standard 1.01

There are many kinds of files. In fact, one of the common ideas in Unixlike operating systems such as Linux is that “everything is a file.” As we proceed with our lessons, we will see just how true that statement is

While many of the files on our system are familiar, for example, MP3 and JPEG files, there are many kinds that are a little less obvious and a few that are quite strange.

Viewing File Contents with less

The less command is a program to view text files. Throughout our Linux system, there are many files that contain human-readable text.

The less program provides a convenient way to examine them. Why would we want to examine text files?

Because many of the files that contain system settings (called configuration files) are stored in this format, and being able to read them gives us insight about how the system works.

In addition, some of the actual programs that the system uses (called scripts) are stored in this format. In later chapters, we will learn how to edit text files in order to modify system settings and write our own scripts, but for now we will just look at their contents.

The less command is used like this:

1

less filename

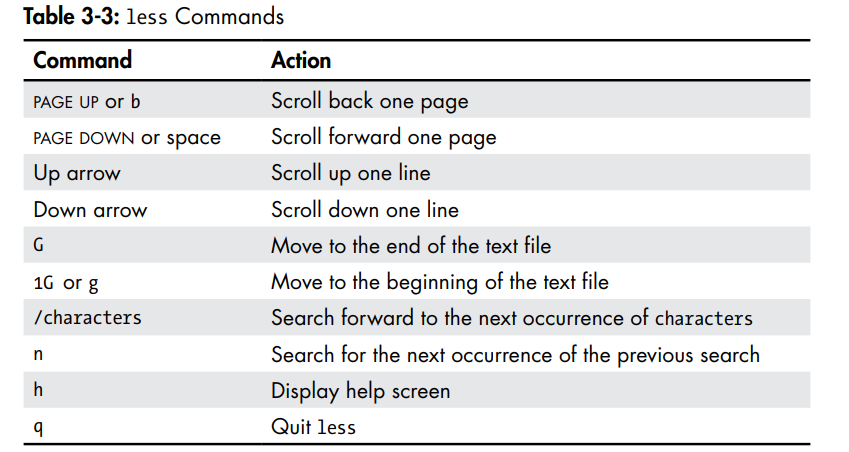

Once started, the less program allows us to scroll forward and backward through a text file. For example, to examine the file that defines all the system’s user accounts, enter the following command:

1

[me@linuxbox ~]$ less /etc/passwd

Once started, the less program allows us to scroll forward and backward through a text file. For example, to examine the file that defines all the system’s user accounts, enter the following command:

Taking a Guided Tour

The file system layout on a Linux system is much like that found on other Unix-like systems. The design is actually specified in a published standard called the Linux Filesystem Hierarchy Standard. Not all Linux distributions conform to the standard exactly, but most come pretty close.

Next, we are going to wander around the file system ourselves to see what makes our Linux system tick. This will give us a chance to practice our navigation skills. One of the things we will discover is that many of the interesting files are in plain human-readable text. As we go about our tour, try the following:

-

cd into a given directory.

-

List the directory contents with ls -l.

-

if you see an interesting file, determine its contents with file

-

if it looks like it might be text, try viewing it with less.

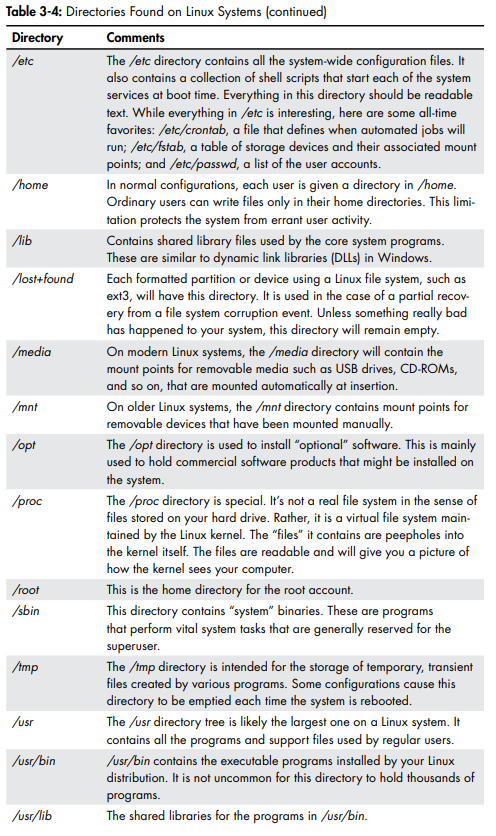

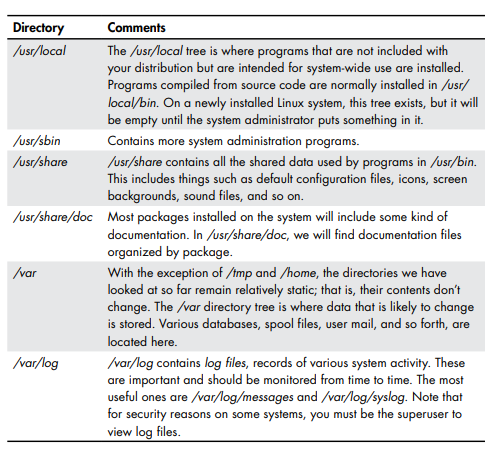

If we accidentally attempt to view a non-text file and it scrambles the terminal window, we can recover by entering the reset command. As we wander around, don’t be afraid to look at stuff. Regular users are largely prohibited from messing things up. That’s the system administrator’s job! If a command complains about something, just move on to something else. Spend some time looking around. The system is ours to explore. Remember, in Linux, there are no secrets! Table 3-4 lists just a few of the directories we can explore. There may be some slight differences depending on our Linux distribution. Don’t be afraid to look around and try more!

Symbolic Links

As we look around, we are likely to see a directory listing (for example, /lib) with an entry like this:

1

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 11 2018-08-11 07:34 libc.so.6 -> libc-2.6.so

Notice how the first letter of the listing is l and the entry seems to have two filenames? This is a special kind of a file called a symbolic link (also known as a soft link or symlink). In most Unix-like systems, it is possible to have a file referenced by multiple names. While the value of this might not be obvious, it is really a useful feature.

Picture this scenario: a program requires the use of a shared resource of some kind contained in a file named “foo,” but “foo” has frequent version changes. It would be good to include the version number in the filename so the administrator or other interested party could see what version of “foo” is installed. This presents a problem. If we change the name of the shared resource, we have to track down every program that might use it and change it to look for a new resource name every time a new version of the resource is installed. That doesn’t sound like fun at all.

Here is where symbolic links save the day. Suppose we install version 2.6 of “foo,” which has the filename “foo-2.6,” and then create a symbolic link simply called “foo” that points to “foo-2.6.” This means that when a program opens the file “foo,” it is actually opening the file “foo-2.6.” Now everybody is happy. The programs that rely on “foo” can find it, and we can still see what actual version is installed. When it is time to upgrade to “foo-2.7,” we just add the file to our system, delete the symbolic link “foo,” and create a new one that points to the new version. Not only does this solve the problem of the version upgrade, it also allows us to keep both versions on our machine. Imagine that “foo-2.7” has a bug (damn those developers!), and we need to revert to the old version. Again, we just delete the symbolic link pointing to the new version and create a new symbolic link pointing to the old version.

The directory listing at the beginning of this section (from the /lib directory of a Fedora system) shows a symbolic link called libc.so.6 that points to a shared library file called libc-2.6.so. This means that programs looking for libc.so.6 will actually get the file libc-2.6.so. We will learn how to create symbolic links in the next chapter.

Hard Links

While we are on the subject of links, we need to mention that there is a second type of link called hard links. Hard links also allow files to have multiple names, but they do it in a different way. We’ll talk more about the differences between symbolic and hard links in the next chapter.

Summing Up

With our tour behind us, we have learned a lot about our system. We’ve seen various files and directories and their contents. One thing you should take away from this is how open the system is. In Linux there are many important files that are plain human-readable text. Unlike many proprietary systems, Linux makes everything available for examination and study.