The Basics

Functions

The main way of getting something done in a C++ program is to call a function to do it. Defining a function is the way you specify how an operation is to be done. A function cannot be called unless it has been previously declared.

A function declaration gives the name of the function, the type of the value returned (if any), and the number and types of the arguments that must be supplied in a call. For example:

1

2

3

Elem∗ next_elem(); // no argument; return a pointer to Elem (an Elem*)

void exit(int); // int argument; return nothing

double sqrt(double); // double argument; return a double

In a function declaration, the return type comes before the name of the function and the argument types come after the name enclosed in parentheses.

The semantics of argument passing are identical to the semantics of initialization (§3.6.1). That is, argument types are checked and implicit argument type conversion takes place when necessary (§1.4). For example:

1

2

double s2 = sqrt(2); // call sqrt() with the argument double{2}

double s3 = sqrt("three"); // error : sqr t() requires an argument of type double

The value of such compile-time checking and type conversion should not be underestimated.

A function declaration may contain argument names. This can be a help to the reader of a program, but unless the declaration is also a function definition, the compiler simply ignores such names. For example:

1

2

double sqrt(double d); // retur n the square root of d

double square(double); // retur n the square of the argument

The type of a function consists of its return type and the sequence of its argument types. For example:

1

double get(const vector<double>& vec, int index); // type: double(const vector<double>&,int)

A function can be a member of a class (§2.3, §4.2.1). For such a member function, the name of its class is also part of the function type. For example:\

1

char& String::operator[](int index); // type: char& String::(int)

We want our code to be comprehensible, because that is the first step on the way to maintainability. The first step to comprehensibility is to break computational tasks into meaningful chunks (represented as functions and classes) and name those. Such functions then provide the basic vocabulary of computation, just as the types (built-in and user-defined) provide the basic vocabulary of data. The C++ standard algorithms (e.g., find, sor t, and iota) provide a good start (Chapter 12). Next, we can compose functions representing common or specialized tasks into larger computations.

The number of errors in code correlates strongly with the amount of code and the complexity of the code. Both problems can be addressed by using more and shorter functions. Using a function to do a specific task often saves us from writing a specific piece of code in the middle of other code; making it a function forces us to name the activity and document its dependencies.

If two functions are defined with the same name, but with different argument types, the compiler will choose the most appropriate function to invoke for each call. For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

void print(int); // takes an integer argument

void print(double); // takes a floating-point argument

void print(string); // takes a string argument

void user()

{

print(42); // calls print(int)

print(9.65); // calls print(double)

print("Barcelona"); // calls print(str ing)

}

If two alternative functions could be called, but neither is better than the other, the call is deemed ambiguous and the compiler gives an error. For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

void print(int,double);

void print(double ,int);

void user2()

{

print(0,0); // error : ambiguous

}

Defining multiple functions with the same name is known as function overloading and is one of the essential parts of generic programming (§7.2). When a function is overloaded, each function of the same name should implement the same semantics. The print() functions are an example of this; each print() prints its argument.

Types, Variables, and Arithmetic

Every name and every expression has a type that determines the operations that may be performed on it. For example, the declaration

1

int inch;

specifies that inch is of type int; that is, inch is an integer variable. A declaration is a statement that introduces an entity into the program. It specifies a type for the entity:

-

A type defines a set of possible values and a set of operations (for an object).

-

An object is some memory that holds a value of some type.

-

A value is a set of bits interpreted according to a type.

-

A variable is a named object

C++ offers a small zoo of fundamental types, but since I’m not a zoologist, I will not list them all. You can find them all in reference sources, such as [Stroustrup,2013] or the [Cppreference] on the Web. Examples are:

1

2

3

4

5

bool // Boolean, possible values are true and false

char // character, for example, 'a', 'z', and '9'

int // integer, for example, -273, 42, and 1066

double // double-precision floating-point number, for example, -273.15, 3.14, and 6.626e-34

unsigned // non-negative integer, for example, 0, 1, and 999 (use for bitwise logical operations)

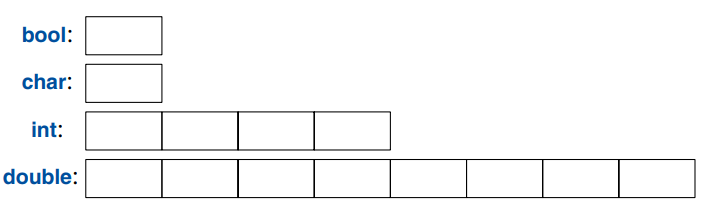

Each fundamental type corresponds directly to hardware facilities and has a fixed size that determines the range of values that can be stored in it:

A char variable is of the natural size to hold a character on a given machine (typically an 8-bit byte), and the sizes of other types are multiples of the size of a char. The size of a type is implementation-defined (i.e., it can vary among different machines) and can be obtained by the siz eof operator; for example, siz eof(char) equals 1 and siz eof(int) is often 4.

Numbers can be floating-point or integers.

-

Floating-point numbers are recognized by a decimal point (e.g., 3.14) or by an exponent (e.g., 3e−2).

-

Integer literals are by default decimal (e.g., 42 means forty-two). A 0b prefix indicates a binary (base 2) integer literal (e.g., 0b10101010). A 0x prefix indicates a hexadecimal (base 16) integer literal (e.g., 0xBAD1234). A 0 prefix indicates an octal (base 8) integer literal (e.g., 0334).

To make long literals more readable for humans, we can use a single quote (‘) as a digit separator. For example, π is about 3.14159’26535’89793’23846’26433’83279’50288 or if you prefer hexadecimal 0x3.243F’6A88’85A3’08D3.

1.4.1 Arithmetic

The arithmetic operators can be used for appropriate combinations of the fundamental types:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

x+y // plus

+x // unar y plus

x−y // minus

−x // unar y minus

x∗y // multiply

x/y // divide

x%y // remainder (modulus) for integers

So can the comparison operators:

1

2

3

4

5

6

x==y // equal

x!=y // not equal

x<y // less than

x>y // greater than

x<=y // less than or equal

x>=y // greater than or equal

Furthermore, logical operators are provided:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

x&y // bitwise and

x|y // bitwise or

xˆy // bitwise exclusive or

˜x // bitwise complement

x&&y // logical and

x||y // logical or

!x // logical not (negation)

| A bitwise logical operator yields a result of the operand type for which the operation has been performed on each bit. The logical operators && and | simply return true or false depending on the values of their operands. |

In assignments and in arithmetic operations, C++ performs all meaningful conversions between the basic types so that they can be mixed freely:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

void some_function() // function that doesn’t return a value

{

double d = 2.2; // initialize floating-point number

int i = 7; // initialize integer

d = d+i; // assign sum to d

i=d∗i; // assign product to i; beware: truncating the double d*i to an int

}

The conversions used in expressions are called the usual arithmetic conversions and aim to ensure that expressions are computed at the highest precision of its operands. For example, an addition of a double and an int is calculated using double-precision floating-point arithmetic.

Note that = is the assignment operator and == tests equality. In addition to the conventional arithmetic and logical operators, C++ offers more specific operations for modifying a variable:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

x+=y // x = x+y

++x // increment: x = x+1

x−=y // x = x-y

−−x // decrement: x = x-1

x∗=y // scaling: x = x*y

x/=y // scaling: x = x/y

x%=y // x = x%y

These operators are concise, convenient, and very frequently used.

The order of evaluation of expressions is left to right, except for assignments, which are right to-left. The order of evaluation of function arguments is unfortunately unspecified.

Initialization

Before an object can be used, it must be given a value. C++ offers a variety of notations for expressing initialization, such as the = used above, and a universal form based on curly-bracedelimited initializer lists:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

double d1 = 2.3; // initialize d1 to 2.3

double d2 {2.3}; // initialize d2 to 2.3

double d3 = {2.3}; // initialize d3 to 2.3 (the = is optional with { ... })

complex<double> z = 1; // a complex number with double-precision floating-point scalars

complex<double> z2 {d1,d2};

complex<double> z3 = {d1,d2}; // the = is optional with { ... }

vector<int> v {1,2,3,4,5,6}; // a vector of ints

The = form is traditional and dates back to C, but if in doubt, use the general {}-list form. If nothing else, it saves you from conversions that lose information:

1

2

int i1 = 7.8; // i1 becomes 7 (surpr ise?)

int i2 {7.8}; // error : floating-point to integer conversion

Unfortunately, conversions that lose information, narrowing conversions, such as double to int and int to char, are allowed and implicitly applied when you use = (but not when you use {}). The problems caused by implicit narrowing conversions are a price paid for C compatibility (§16.3).

A constant (§1.6) cannot be left uninitialized and a variable should only be left uninitialized in extremely rare circumstances. Don’t introduce a name until you have a suitable value for it. Userdefined types (such as string, vector, Matrix, Motor_controller, and Orc_warrior) can be defined to be implicitly initialized (§4.2.1).

When defining a variable, you don’t need to state its type explicitly when it can be deduced from the initializer:

1

2

3

4

5

6

auto b = true; // a bool

auto ch = 'x'; // a char

auto i = 123; // an int

auto d = 1.2; // a double

auto z = sqrt(y); // z has the type of whatever sqr t(y) retur ns

auto bb {true}; // bb is a bool

With auto, we tend to use the = because there is no potentially troublesome type conversion involved, but if you prefer to use {} initialization consistently, you can do that instead.

We use auto where we don’t have a specific reason to mention the type explicitly. ‘‘Specific reasons’’ include:

-

The definition is in a large scope where we want to make the type clearly visible to readers of our code

-

We want to be explicit about a variable’s range or precision (e.g., double rather than float).

Using auto, we avoid redundancy and writing long type names. This is especially important in generic programming where the exact type of an object can be hard for the programmer to know and the type names can be quite long (§12.2).

Scope and Lifetime

A declaration introduces its name into a scope:

-

Local scope: A name declared in a function (§1.3) or lambda (§6.3.2) is called a local name. Its scope extends from its point of declaration to the end of the block in which its declaration occurs. A block is delimited by a { } pair. Function argument names are considered local names.

-

Class scope: A name is called a member name (or a class member name) if it is defined in a class (§2.2, §2.3, Chapter 4), outside any function (§1.3), lambda (§6.3.2), or enum class (§2.5). Its scope extends from the opening { of its enclosing declaration to the end of that declaration.

-

Namespace scope: A name is called a namespace member name if it is defined in a namespace (§3.4) outside any function, lambda (§6.3.2), class (§2.2, §2.3, Chapter 4), or enum class (§2.5). Its scope extends from the point of declaration to the end of its namespace.

A name not declared inside any other construct is called a global name and is said to be in the global namespace

In addition, we can have objects without names, such as temporaries and objects created using new (§4.2.2). For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

vector<int> vec; // vec is global (a global vector of integers)

struct Record {

string name; // name is a member or Record (a string member)

// ...

};

void fct(int arg) // fct is global (a global function)

// arg is local (an integer argument)

{

string motto {"Who dares wins"}; // motto is local

auto p = new Record{"Hume"}; // p points to an unnamed Record (created by new)

// ...

}

An object must be constructed (initialized) before it is used and will be destroyed at the end of its scope. For a namespace object the point of destruction is the end of the program. For a member, the point of destruction is determined by the point of destruction of the object of which it is a member. An object created by new ‘‘lives’’ until destroyed by delete (§4.2.2).