C++ supports two notions of immutability:

-

const: meaning roughly ‘‘I promise not to change this value.’’ This is used primarily to specify interfaces so that data can be passed to functions using pointers and references without fear of it being modified. The compiler enforces the promise made by const. The value of a const can be calculated at run time

-

constexpr: meaning roughly ‘‘to be evaluated at compile time.’’ This is used primarily to specify constants, to allow placement of data in read-only memory (where it is unlikely to be corrupted), and for performance. The value of a constexpr must be calculated by the compiler.

For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

constexpr int dmv = 17; // dmv is a named constant

int var = 17; // var is not a constant

const double sqv = sqrt(var); // sqv is a named constant, possibly computed at run time

double sum(const vector<double>&); // sum will not modify its argument (§1.7)

vector<double> v {1.2, 3.4, 4.5}; // v is not a constant

const double s1 = sum(v); // OK: sum(v) is evaluated at run time

constexpr double s2 = sum(v); // error : sum(v) is not a constant expression

1

2

3

4

constexpr double square(double x) { return x∗x; }

constexpr double max1 = 1.4∗square(17); // OK 1.4*square(17) is a constant expression

constexpr double max2 = 1.4∗square(var); // error : var is not a constant expression

const double max3 = 1.4∗square(var); // OK, may be evaluated at run time

A constexpr function can be used for non-constant arguments, but when that is done the result is not a constant expression. We allow a constexpr function to be called with non-constant-expression arguments in contexts that do not require constant expressions. That way, we don’t hav e to define essentially the same function twice: once for constant expressions and once for variables.

To be constexpr, a function must be rather simple and cannot have side effects and can only use information passed to it as arguments. In particular, it cannot modify non-local variables, but it can have loops and use its own local variables. For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

constexpr double nth(double x, int n) // assume 0<=n

{

double res = 1;

int i = 0;

while (i<n) { // while-loop: do while the condition is true (§1.7.1)

res∗=x;

++i;

}

return res;

}

In a few places, constant expressions are required by language rules (e.g., array bounds (§1.7), case labels (§1.8), template value arguments (§6.2), and constants declared using constexpr). In other cases, compile-time evaluation is important for performance. Independently of performance issues, the notion of immutability (an object with an unchangeable state) is an important design concern

Pointers, Arrays and References

The most fundamental collection of data is a contiguously allocated sequence of elements of the same type, called an array. This is basically what the hardware offers. An array of elements of type char can be declared like this:

1

char v[6]; // array of 6 characters

Similarly, a pointer can be declared like this:

1

char∗ p; // pointer to character

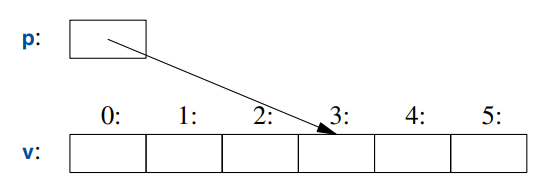

In declarations, [ ] means ‘‘array of’’ and ∗ means ‘‘pointer to.’’ All arrays have 0 as their lower bound, so v has six elements, v[0] to v[5]. The size of an array must be a constant expression (§1.6). A pointer variable can hold the address of an object of the appropriate type:

1

2

char∗ p = &v[3]; // p points to v’s four th element

char x = ∗p; // *p is the object that p points to

In an expression, prefix unary ∗ means ‘‘contents of’’ and prefix unary & means ‘‘address of.’’ We can represent the result of that initialized definition graphically:

Consider copying ten elements from one array to another:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

void copy_fct()

{

int v1[10] = {0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9};

int v2[10]; // to become a copy of v1

for (auto i=0; i!=10; ++i) // copy elements

v2[i]=v1[i];

// ...

}

This for-statement can be read as ‘‘set i to zero; while i is not 10, copy the ith element and increment i.’’ When applied to an integer or floating-point variable, the increment operator, ++, simply adds 1. C++ also offers a simpler for-statement, called a range-for-statement, for loops that traverse a sequence in the simplest way:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

void print()

{

int v[] = {0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9};

for (auto x : v) // for each x in v

cout << x << '\n';

for (auto x : {10,21,32,43,54,65})

cout << x << '\n';

// ...

}

The first range-for-statement can be read as ‘‘for every element of v, from the first to the last, place a copy in x and print it.’’ Note that we don’t hav e to specify an array bound when we initialize it with a list. The range-for-statement can be used for any sequence of elements (§12.1).

If we didn’t want to copy the values from v into the variable x, but rather just have x refer to an element, we could write:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

void increment()

{

int v[] = {0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9};

for (auto& x : v) // add 1 to each x in v

++x;

// ...

}

In a declaration, the unary suffix & means ‘‘reference to.’’ A reference is similar to a pointer, except that you don’t need to use a prefix ∗ to access the value referred to by the reference. Also, a reference cannot be made to refer to a different object after its initialization. References are particularly useful for specifying function arguments.

For example:

1

void sort(vector<double>& v); // sor t v (v is a vector of doubles)

By using a reference, we ensure that for a call sor t(my_vec), we do not copy my_vec and that it really is my_vec that is sorted and not a copy of it.

When we don’t want to modify an argument but still don’t want the cost of copying, we use a const reference (§1.6). For example:

1

double sum(const vector<double>&)

Functions taking const references are very common. When used in declarations, operators (such as &, ∗, and [ ]) are called declarator operators:

1

2

3

4

T a[n] // T[n]: a is an array of n Ts

T∗ p // T*: p is a pointer to T

T& r // T&: r is a reference to T

T f(A) // T(A): f is a function taking an argument of type A returning a result of type T

The Null Pointer

We try to ensure that a pointer always points to an object so that dereferencing it is valid. When we don’t hav e an object to point to or if we need to represent the notion of ‘‘no object available’’ (e.g., for an end of a list), we give the pointer the value nullptr (‘‘the null pointer’’). There is only one nullptr shared by all pointer types:

1

2

3

double∗ pd = nullptr;

Link<Record>∗ lst = nullptr; // pointer to a Link to a Record

int x = nullptr; // error : nullptr is a pointer not an integer

It is often wise to check that a pointer argument actually points to something:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

int count_x(const char∗ p, char x)

// count the number of occurrences of x in p[]

// p is assumed to point to a zero-ter minated array of char (or to nothing)

{

if (p==nullptr)

return 0;

int count = 0;

for (; ∗p!=0; ++p)

if (∗p==x)

++count;

return count;

}

Note how we can advance a pointer to point to the next element of an array using ++ and that we can leave out the initializer in a for-statement if we don’t need it.

The definition of count_x() assumes that the char∗ is a C-style string, that is, that the pointer points to a zero-terminated array of char. The characters in a string literal are immutable, so to handle count_x(“Hello!”), I declared count_x() a const char∗ argument.

In older code, 0 or NULL is typically used instead of nullptr. Howev er, using nullptr eliminates potential confusion between integers (such as 0 or NULL) and pointers (such as nullptr). In the count_x() example, we are not using the initializer part of the for-statement, so we can use the simpler while-statement:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

int count_x(const char∗ p, char x)

// count the number of occurrences of x in p[]

// p is assumed to point to a zero-ter minated array of char (or to nothing)

{

if (p==nullptr)

return 0;

int count = 0;

while (∗p) {

if (∗p==x)

++count;

++p;

}

return count;

}

The while-statement executes until its condition becomes false.

A test of a numeric value (e.g., while (∗p) in count_x()) is equivalent to comparing the value to 0 (e.g., while (∗p!=0)). A test of a pointer value (e.g., if (p)) is equivalent to comparing the value to nullptr (e.g., if (p!=nullptr)).

There is no ‘‘null reference.’’ A reference must refer to a valid object (and implementations assume that it does). There are obscure and clever ways to violate that rule; don’t do that.

Tests

C++ provides a conventional set of statements for expressing selection and looping, such as ifstatements, switch-statements, while-loops, and for-loops. For example, here is a simple function that prompts the user and returns a Boolean indicating the response:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

bool accept()

{

cout << "Do you want to proceed (y or n)?\n"; // wr ite question

char answer = 0; // initialize to a value that will not appear on input

cin >> answer; // read answer

if (answer == 'y')

return true;

return false;

}

To match the « output operator (‘‘put to’’), the » operator (‘‘get from’’) is used for input; cin is the standard input stream (Chapter 10). The type of the right-hand operand of » determines what input is accepted, and its right-hand operand is the target of the input operation. The \n character at the end of the output string represents a newline (§1.2.1).

Note that the definition of answer appears where it is needed (and not before that).

The example could be improved by taking an n (for ‘‘no’’) answer into account:A declaration can appear anywhere a statement can.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

bool accept2()

{

cout << "Do you want to proceed (y or n)?\n"; // wr ite question

char answer = 0; // initialize to a value that will not appear on input

cin >> answer; // read answer

switch (answer) {

case 'y':

return true;

case 'n':

return false;

default:

cout << "I'll take that for a no.\n";

return false;

}

}

A switch-statement tests a value against a set of constants. Those constants, called case-labels, must be distinct, and if the value tested does not match any of them, the default is chosen. If the value doesn’t match any case-label and no default is provided, no action is taken .

We don’t hav e to exit a case by returning from the function that contains its switch-statement. Often, we just want to continue execution with the statement following the switch-statement. We can do that using a break statement. As an example, consider an overly clever, yet primitive, parser for a trivial command video game:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

void action()

{

while (true) {

cout << "enter action:\n"; // request action

string act;

cin >> act; // read characters into a string

Point delta {0,0}; // Point holds an {x,y} pair

for (char ch : act) {

switch (ch) {

case 'u': // up

case 'n': // nor th

++delta.y;

break;

case 'r': // right

case 'e': // east

++delta.x;

break;

// ... more actions ...

default:

cout << "I freeze!\n";

}

move(current+delta∗scale);

update_display();

}

}

}

Like a for-statement (§1.7), an if-statement can introduce a variable and test it. For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

void do_something(vector<int>& v)

{

if (auto n = v.siz e(); n!=0) {

// ... we get here if n!=0 ...

}

// ...

}

Here, the integer n is defined for use within the if-statement , initialized with v.siz e(), and immediately tested by the n!=0 condition after the semicolon. A name declared in a condition is in scope on both branches of the if-statement.

As with the for-statement, the purpose of declaring a name in the condition of an if-statement is to keep the scope of the variable limited to improve readability and minimize errors. The most common case is testing a variable against 0 (or the nullptr). To do that, simply leave out the explicit mention of the condition. For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

void do_something(vector<int>& v)

{

if (auto n = v.siz e()) {

// ... we get here if n!=0 ...

}

// ...

}

Prefer to use this terser and simpler form when you can.

Mapping the Hardware

C++ offers a direct mapping to hardware. When you use one of the fundamental operations, the implementation is what the hardware offers, typically a single machine operation. For example, adding two ints, x+y executes an integer add machine instruction.

A C++ implementation sees a machine’s memory as a sequence of memory locations into which it can place (typed) objects and address them using pointers:

A pointer is represented in memory as a machine address, so the numeric value of p in this figure would be 3. If this looks much like an array (§1.7), that’s because an array is C++’s basic abstraction of ‘‘a contiguous sequence of objects in memory.’’

The simple mapping of fundamental language constructs to hardware is crucial for the raw lowlevel performance for which C and C++ have been famous for decades. The basic machine model of C and C++ is based on computer hardware, rather than some form of mathematics.

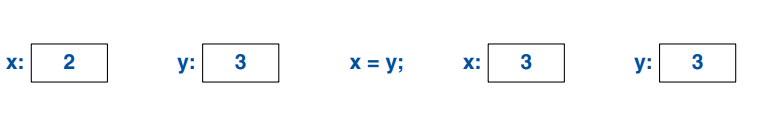

Assignment

An assignment of a built-in type is a simple machine copy operation. Consider:

1

2

3

4

int x = 2;

int y = 3;

x = y; // x becomes 3

// Note: x==y

This is obvious. We can graphically represent that like this:

Note that the two objects are independent. We can change the value of y without affecting the value of x. For example x=99 will not change the value of y. Unlike Java, C#, and other languages, but like C, that is true for all types, not just for ints.

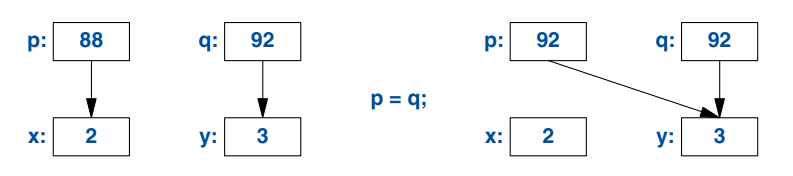

If we want different objects to refer to the same (shared) value, we must say so. We could use pointers

We can represent that graphically like this:

I arbitrarily chose 88 and 92 as the addresses of the ints. Again, we can see that the assigned-to object gets the value from the assigned object, yielding two independent objects (here, pointers), with the same value. That is, p=q gives p==q. After p=q, both pointers point to y.

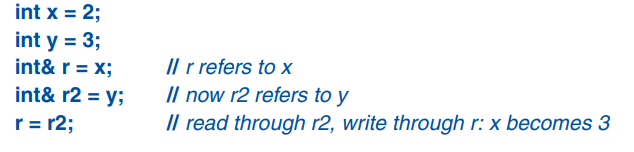

A reference and a pointer both refer/point to an object and both are represented in memory as a machine address. However, the language rules for using them differ. Assignment to a reference does not change what the reference refers to but assigns to the referenced object:

1

2

3

4

5

int x = 2;

int y = 3;

int& r = x; // r refers to x

int& r2 = y; // now r2 refers to y

r = r2; // read through r2, write through r: x becomes 3

We can represent that graphically like this:

To access the value pointed to by a pointer, you use ∗; that is automatically (implicitly) done for a reference.

After x=y, we hav e x==y for every built-in type and well-designed user-defined type (Chapter 2) that offers = (assignment) and == (equality comparison).

Initialization

Initialization differs from assignment. In general, for an assignment to work correctly, the assigned-to object must have a value. On the other hand, the task of initialization is to make an uninitialized piece of memory into a valid object. For almost all types, the effect of reading from or writing to an uninitialized variable is undefined. For built-in types, that’s most obvious for references:

1

2

3

4

5

int x = 7;

int& r {x}; // bind r to x (r refers to x)

r = 7; // assign to whatever r refers to

int& r2; // error : uninitialized reference

r2 = 99; // assign to whatever r2 refers to

Fortunately, we cannot have an uninitialized reference; if we could, then that r2=99 would assign 99 to some unspecified memory location; the result would eventually lead to bad results or a crash. You can use = to initialize a reference but please don’t let that confuse you. For example:

1

int& r = x; // bind r to x (r refers to x)

This is still initialization and binds r to x, rather than any form of value copy

The distinction between initialization and assignment is also crucial to many user-defined types, such as string and vector, where an assigned-to object owns a resource that needs to eventually be released (§5.3).

The basic semantics of argument passing and function value return are that of initialization (§3.6). For example, that’s how we get pass-by-reference.