Modularity - 2

Separate Compilation

C++ supports a notion of separate compilation where user code sees only declarations of the types and functions used. The definitions of those types and functions are in separate source files and are compiled separately. This can be used to organize a program into a set of semi-independent code fragments. Such separation can be used to minimize compilation times and to strictly enforce separation of logically distinct parts of a program (thus minimizing the chance of errors). A library is often a collection of separately compiled code fragments (e.g., functions).

Typically, we place the declarations that specify the interface to a module in a file with a name indicating its intended use. For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

// Vector.h:

class Vector {

public:

Vector(int s);

double& operator[](int i);

int size();

private:

double∗ elem; // elem points to an array of sz doubles

int sz;

};

This declaration would be placed in a file Vector.h. Users then include that file, called a header file, to access that interface. For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

// user.cpp:

#include "Vector.h" // get Vector’s interface

#include <cmath> // get the standard-librar y math function interface including sqrt()

double sqrt_sum(Vector& v)

{

double sum = 0;

for (int i=0; i!=v.siz e(); ++i)

sum+=std::sqr t(v[i]); // sum of square roots

return sum;

}

To help the compiler ensure consistency, the .cpp file providing the implementation of Vector will also include the .h file providing its interface:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

// Vector.cpp:

#include "Vector.h" // get Vector’s interface

Vector::Vector(int s)

:elem{new double[s]}, sz{s} // initialize members

{

}

double& Vector::operator[](int i)

{

return elem[i];

}

int Vector::siz e()

{

return sz;

}

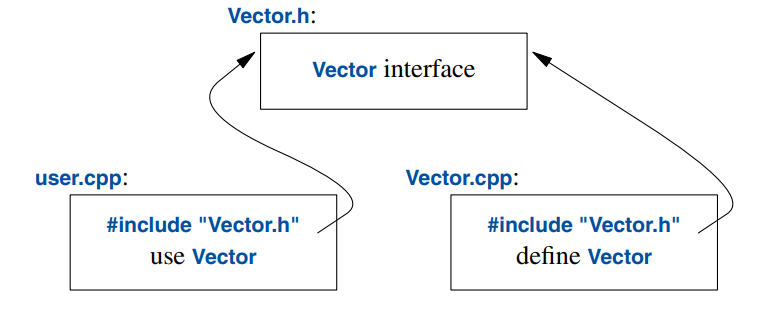

The code in user.cpp and Vector.cpp shares the Vector interface information presented in Vector.h,

but the two files are otherwise independent and can be separately compiled. Graphically, the program fragments can be represented like this:

Strictly speaking, using separate compilation isn’t a language issue; it is an issue of how best to take advantage of a particular language implementation. However, it is of great practical importance. The best approach to program organization is to think of the program as a set of modules with well-defined dependencies, represent that modularity logically through language features, and then exploit the modularity physically through files for effective separate compilation.

A .cpp file that is compiled by itself (including the h files it #includes) is called a translation unit. A program can consist of many thousand translation units.

Modules(C++20)

The use of #includes is a very old, error-prone, and rather expensive way of composing programs out of parts. If you #include header.h in 101 translation units, the text of header.h will be processed by the compiler 101 times. If you #include header1.h before header2.h the declarations and macros in header1.h might affect the meaning of the code in header2.h. If instead you #include header2.h before header1.h, it is header2.h that might affect the code in header1.h. Obviously, this is not ideal, and in fact it has been a major source of cost and bugs since 1972 when this mechanism was first introduced into C.

We are finally about to get a better way of expressing physical modules in C++. The language feature, called modules is not yet ISO C++, but it is an ISO Technical Specification [ModulesTS] and will be part of C++20. Implementations are in use, so I risk recommending it here even though details are likely to change and it may be years before everybody can use it in production code. Old code, in this case code using #include, can ‘‘live’’ for a very long time because it can be costly and time consuming to update.

Consider how to express the Vector and sqr t_sum() example from §3.2 using modules:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

// file Vector.cpp:

module; // this compilation will define a module

// ... here we put stuff that Vector might need for its implementation ...

expor t module Vector; // defining the module called "Vector"

expor t class Vector {

public:

Vector(int s);

double& operator[](int i);

int size();

private:

double∗ elem; // elem points to an array of sz doubles

int sz;

};

Vector::Vector(int s)

:elem{new double[s]}, sz{s} // initialize members

{

}

double& Vector::operator[](int i)

{

return elem[i];

}

int Vector::siz e()

{

return sz;

}

expor t int size(const Vector& v) { return v.siz e(); }

This defines a module called Vector, which exports the class Vector, all its member functions, and the non-member function siz e().

The way we use this module is to impor t it where we need it. For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

// file user.cpp:

impor t Vector; // get Vector’s interface

#include <cmath> // get the standard-librar y math function interface including sqrt()

double sqrt_sum(Vector& v)

{

double sum = 0;

for (int i=0; i!=v.siz e(); ++i)

sum+=std::sqr t(v[i]); // sum of square roots

return sum;

}

I could have impor ted the standard library mathematical functions also, but I used the old-fashioned #include just to show that you can mix old and new. Such mixing is essential for gradually upgrading older code from using #include to import.

The differences between headers and modules are not just syntactic.

-

A module is compiled once only (rather than in each translation unit in which it is used).

-

Two modules can be impor ted in either order without changing their meaning.

-

If you import something into a module, users of your module do not implicitly gain access to (and are not bothered by) what you imported: impor t is not transitive.

The effects on maintainability and compile-time performance can be spectacular.